|

If Harvard and Wharton had not been charmed by the Lalu Prasad of popular folklore a few years ago and had, instead, wanted to study how real change was possible within the government of India, they would have looked at a fascinating experiment in New Delhi called the ministry of overseas Indian affairs. Few people — even within the government, leave alone those outside it — are aware that this full-fledged ministry is run out of just one floor of a building in the capital’s diplomatic area of Chanakyapuri with a full-time staff of merely 29 people of the rank of section officers and above.

|

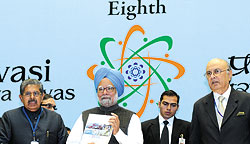

Opening ceremony of Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, 2010 |

Since the 1960s, when Indira Gandhi tried to enforce belt-tightening within the administration, efforts have been made and unmade to cut waste, frown upon bloated bureaucracy and ensure a small but result-oriented government. But with each such effort, the government has only become bigger and arguably less efficient. The commissions set up for administrative reforms have also had mixed results.

What makes the MOIA experiment truly fascinating in the backdrop of half-hearted efforts to improve governance all over the country is that, of its 29 permanent posts, three positions of under-secretaries have been lying vacant and one man has been holding the dual job of both the joint-secretary-level posts that exist in this ministry. There would be few other examples anywhere in the world of a ministry being managed with 25 officers, half of them mere section officers or under-secretaries.

Bear in mind that this is a ministry which has become a clearing house for everything to do with25 million people worldwide of Indian origin, a majority of whom are insufferably demanding and think that they have a greater claim on India and its resources because of their non-resident status, and a broad picture emerges of the workload that burdens the MOIA.

The story of this ministry becomes all the more fascinating because of its leadership in the last four and a half of the MOIA’s six-year existence. Vayalar Ravi is one of the Congress’s grassroots leaders, having won the popular mandate by successfully contesting for both the state assembly and the Lok Sabha several times. As a trade union leader, he once controlled some of the most powerful unions in his home state of Kerala where he was home minister. He was one of the founders — along with the defence minister, A.K. Antony — of the Kerala Students Union, the Congress’s student wing, which played a huge role in unseating the first communist government in the state in 1959. The story of this ministry becomes all the more fascinating because of its leadership in the last four and a half of the MOIA’s six-year existence. Vayalar Ravi is one of the Congress’s grassroots leaders, having won the popular mandate by successfully contesting for both the state assembly and the Lok Sabha several times. As a trade union leader, he once controlled some of the most powerful unions in his home state of Kerala where he was home minister. He was one of the founders — along with the defence minister, A.K. Antony — of the Kerala Students Union, the Congress’s student wing, which played a huge role in unseating the first communist government in the state in 1959.

Ravi is also a most unlikely candidate, both by temperament and by ideology, for introducing corporate-style management into the running of a ministry or demanding strict accountability in its working. But the MOIA’s “Result Framework Document for 2009-10” is a model even for Western governments, which hold accountability as sacrosanct, to go by. Complete with charts and tables, which list key objectives of his ministry, success indicators and targets, it provides a guide in tangible terms to what is being achieved in the MOIA.

This ministry is a case study for administrative reforms because its short history tells a tale of what ails Indian civil service today. In six years, this ministry has had five secretaries, the average incumbency having been 14 months as against three years in most other ministries at the Centre. Why? Because the MOIA has one of the smallest budgets within the government.

Increasingly, government secretaries from the Indian administrative service want to secure their future as they hurtle towards retirement, and sadly, they often do so by offering patronage that will ensure post-superannuation careers: an Indian variant of the ‘revolving door’ in the American system. The MOIA offers virtually no opportunities for either patronage or benefaction of the kind they seek, and its small budget means not having the power to be profligate with taxpayers’ money. As a result, IAS officers who have just become secretaries go to the MOIA, using it as a parking place and quickly migrate elsewhere in Delhi at the first opportunity. What this has meant is that the functional leadership and responsibility of the MOIA has been with Ravi as minister and the small team down the line, which has been his core group.

When this ministry embarks on global enterprises, such as the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas, an annual gathering of overseas Indians, or mini PBDs in cities like Singapore and New York, it overcomes its small size and limited facilities by outsourcing the job of organizing the bandobast for these events while retaining intellectual control over the proceedings. It is remarkable that even in doing so, the MOIA has done what many others in the capital would have thought impossible. It has secured peace between two organizations to which such work is outsourced — the Confederation of Indian Industry and the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, which are perennially at each other’s throats. As a solution to their rivalry, Ravi ruled that FICCI would handle the PBDs for three years in a row, and for the following three years the job would be given to CII.

Colloquially, this ministry is credited with having coined the term, ‘Bollygarchs’, a reference to the Indian-origin billionaires overseas whose number is on the rise. The Bollygarchs may be happy to be symbolically traced back to Bollywood, but are unlikely to be as pleased to be linked to the Russian oligarchs, whose rise parallels in time with the rise of the super-rich Indian diaspora.

An unfortunate result of India’s economic reforms has been the impression that the government is now for the rich, who have been unfettered by the liberalization. It is an impression that has been strengthened by the celebrity media coverage of the Mittals, the Mallyas and others from the corporate world, some of whom have strayed into national politics.

In such an environment, Ravi has managed to keep his ministry loyal to the values and style of the Indira Gandhi era when the late prime minister sought to identify her government as one which empathized with the underprivileged and sought to be the guardian of their interests. The story of how Ravi pursued every concerned minister without respite until the Union cabinet agreed last year to create an Indian community welfare fund for expatriate labourers in distress is a remarkable example of a member of the council of ministers still standing up for the voiceless. The fund was created to provide shelter, medical care, air passage for repatriation and legal assistance for abused Indian workers overseas and for airlifting their bodies in the event of death.

The welfare fund administered by the MOIA went into operation through Indian missions from January this year, but is confined to 17 countries to which emigration clearance is required when poor and often illiterate workers go to take up jobs, mostly as labourers. It is not available in the United States of America, for instance, where Indians are better off compared to the construction workers who toil in Saudi Arabia.

Similarly, in several countries that are notorious for their low level of labour protection, the MOIA has got local governments to commit themselves to bilateral memoranda of understanding to ensure some form of welfare for Indians at the lowest strata of social order. It is a measure of the difficulties in improving the lot of Indian labour in countries like the United Arab Emirates that only MoUs have been possible with them and not agreements, but at least that is a modest beginning.

The biggest longer-term contribution of this young ministry towards institutionalizing the role of eminent people of Indian origin in building a 21st-century India may lie in having created a global advisory council of overseas Indians to periodically interact with the prime minister, senior cabinet ministers and the foreign and finance secretaries. Among its 25 members are Nobel-prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, management expert Rajat Gupta, industrialist L.N. Mittal, diplomat Kishore Mahbubani and academician Jagdish Bhagwati. The MOIA hopes that the council, which has met a few times since it was set up last year, will “serve as a platform for the prime minister to draw upon the experience, knowledge and wisdom of the best Indian minds wherever they may be based”.

|